500+ Google Reviews

★★★★★ 4.9/5

4.9 out of 5

The best physios by far...

Truly outstanding experience...

...very friendly and welcoming.

...tons of experience.

...they have been amazing.

Pelvic pain affects many groups of people, but is most commonly experienced by either ante-natal or post-natal women. Our expert Physiotherapists have years of experience in treating pelvic pain, helping women both during pregnancy and after.

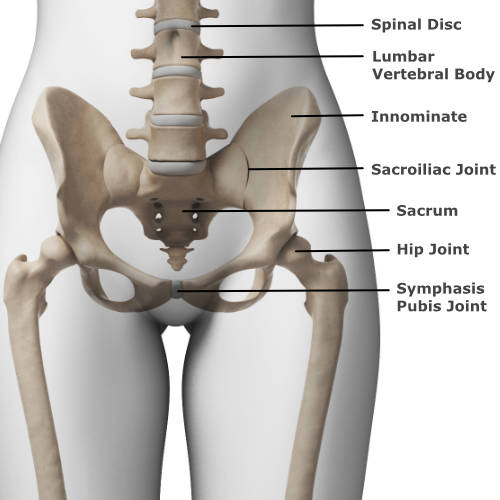

The skeleton of the pelvis is a basin shaped ring of bones connecting the spine to the lower body. The pelvic ring consists of four bones – a right and left hip bone (called innominates) on either side, the sacrum at the very base of the spine, and the coccyx just below the sacrum. The joint at the front of the pelvic ring is called the symphasis-pubis joint. A wedge of cartilage sits between each bone at the centre. At the back, the large right and left hip bones attach to the sacrum, and these are called the sacro-iliac joints.

The skeleton of the pelvis is a basin shaped ring of bones connecting the spine to the lower body. The pelvic ring consists of four bones – a right and left hip bone (called innominates) on either side, the sacrum at the very base of the spine, and the coccyx just below the sacrum. The joint at the front of the pelvic ring is called the symphasis-pubis joint. A wedge of cartilage sits between each bone at the centre. At the back, the large right and left hip bones attach to the sacrum, and these are called the sacro-iliac joints.

The pelvic girdle is a strong structure and only a very small amount of movement normally occurs at the sacro-iliac joints and the symphasis-pubis joint. A vast arrangement of ligaments attach all of the bones together to provide stability across the whole pelvis. Load is distributed through these structures as you do everyday movements including walking, standing and going up/down stairs.

Important muscles around the pelvis include the deep pelvic floor muscles that control integral functions like the flow of urine. Other deep muscles help to stabilise the hip and pelvis. More superficial muscles include the large and powerful gluteal muscles at the back, and to the front of the pelvis, the muscles of the thigh attach at various points.

A complex network of nerves and blood vessels pass throughout the pelvic ring, both in the deep sections of the pelvis and closer to the skin. Fluids including blood, and various electrical signals are carried in these vessels to various parts of the body from the pelvis.

Pelvic pain affects many groups of people, but is most commonly experienced by either ante-natal or post-natal women. This is due to the considerable effects of pregnancy on the lower back and pelvic regions.

About 1 in 5 pregnant women experience discomfort around the front and back of their pelvis during pregnancy. Pain and tenderness may be felt in the back, buttock and leg and/or pain in the groin and pubic region. In pregnancy a hormone called relaxin causes increased flexibility in your ligaments and other soft tissues, allowing space for your baby to grow within your pelvis. The ligaments and muscles that support your pubic bone become lax, allowing your pelvis to move more than normal. In some people this extra movement can cause pain and instability. The increasing weight of your bump can also lead to increased pressure and strain through some of the joints in the lower back and pelvis. The alignment of the pelvis also changes slightly in pregnancy, and this change in posture can lead to pelvic pain too.

Symptoms usually disappear shortly after giving birth. However, some women can suffer for several months afterwards. It can take up to six months before the pelvic joints are completely restored to their normal state. Throughout the pregnancy, Physiotherapy can be extremely effective in both teaching you how best to manage your pelvic symptoms, and also in providing hands on treatment. Do not suffer in silence! There is help to be had and your pregnancy experience can be much better by getting specialist advice and treatment.

Pelvic Floor Dysfunction

The PFM (pelvic floor muscles) are a group of muscles spanning from the sacrum and coccyx at the back of the pelvis, to the pubic bone at the front of the pelvis. The PFM attach both directly and via ligaments and fascia to the pelvic bones. The pelvic organs are located directly above the PFM with the bladder in front, the uterus in the middle and rectum at the back. The urinary passage (urethra), vagina and anus pass through the PFM.

The PFM are constantly working and react to increases in abdominal pressure to compress and lift the urethra, vagina and anus. During pregnancy the PFM weaken due to hormones increasing the flexibility of the supportive ligaments and fascia, and the increasing weight of the growing foetus. Many women experience stretching, weakness and injury to the PFM during labour. If your ‘core’ deep abdominal (transversus abdominus) muscles or gluteal muscles are weak, you might experience less automatic activation in the PFM.

If the PFM is weak or less active you may be at risk of treatable conditions such as:

Pregnant and postnatal women are therefore more at risk of developing PFM dysfunction. PFM exercises through pregnancy will limit the decline in strength during pregnancy, reduce the risk of incontinence and prolapse and facilitate a faster recovery postpartum.

In pregnancy, physiotherapy will help you develop your core to your full potential. A specialised pelvic floor physiotherapist will visualise the perineum (outside of the vagina/back passage) to determine if you are correctly exercising the PFM and give you advice on how to improve your PFM symptoms antenatally. Postnatally a vaginal assessment will more accurately determine the strength and activation of the PFM and help to target exercise to facilitate your recovery.

Link to pelvic floor training central health and POGP pelvic floor leaflet

What is Urinary incontinence?

Urinary incontinence is involuntary leaking of urine- even drops! Common types of incontinence include:

Urinary incontinence may be common but is not normal and is often treatable with physiotherapy. If you do not progress as expected your physiotherapist will discuss other medical options and provide recommendations for referral onwards as you wish.

Link for Bladder and Bowel UK https://www.bbuk.org.uk/adults/adults-bladder/

Link for POGP leaflet on continence https://pogp.csp.org.uk/system/files/publication_files/POGP-Continence.pdf

What is faecal and flatus incontinence?

In pregnancy and postnatally women are more at risk of anal incontinence due to abdominal and baby pressure stretching the nerves and muscles that support the back passage. Common types of anal incontinence include:

It is important to consult with your doctor to eliminate a reversible cause for new or persistent symptoms of anal incontinence prior to physiotherapy treatment. Your doctor may refer you for ultrasound scans and anal physiology tests which provide more information on any injury you may have sustained.

Anal incontinence is less common but occurs in up to 26% of postnatal women. Symptoms often improve significantly with physiotherapy treatment.

Link for Bladder and Bowel UK https://www.bbuk.org.uk/adults/adults-bowel/

Link for POGP https://pogp.csp.org.uk/system/files/publication_files/POGP-Continence.pdf

What is vaginal prolapse?

Vaginal prolapse is a collagen disorder involving stretching or damage to the fascia which supports the vaginal walls. This results in lengthening of the vaginal walls which you may feel as a bulge in the vagina. Often the bulge is accompanied by a sense of heaviness or a sensation of ‘something falling out of the vagina’ much like a tampon slipping.

Vaginal prolapse may develop in pregnancy but more commonly in the first 6 weeks after vaginal delivery. It is estimated that 50% of women with children have some degree of prolapse, but many have no symptoms at all through life or until they are much older. Types of vaginal prolapse include:

Development of prolapse is associated with heavy lifting, straining to empty your bowels and excessive abdominal weight.

Prevention is better than cure, but if you have developed a prolapse, physiotherapy will help to improve muscle supports and advise on safe exercise with the aim to reduce or cure symptoms and prevent the prolapse from worsening over the years.

Link for POGP leaflet https://pogp.csp.org.uk/system/files/pogp-prolapse.pdf

The abdominal wall consists of several layers of muscle surrounded by fascia, joining in the middle to form a central tendon called the linea alba. The deepest and postural muscle layer, the transversus abdominus muscle, creates tension along the linea alba. This compresses the abdominal contents and allows the power generating abdominal muscles (the internal and external oblique and the rectus abdominus muscles) to work more effectively.

In pregnancy, raised levels of relaxin hormone and the growing baby result in an average stretch of 3cm to the linea alba. The fascia is more likely to become thinner and lose elasticity with a larger stretch. Multiple pregnancies, polyhydramnios (excessive amniotic fluid) and large babies, as well as regular heavy lifting, are suggested risk factors for developing DRA.

After pregnancy most will recover in the first 6 months, with about a third experiencing DRA at 12 months. The definition of DRA varies but is generally 2cm or wider. Emerging research suggests the ability to produce tension at the linea alba may be more important than the separation width, for the appearance and function of the abdominal wall.

Prevention and Rehabilitation

Regular exercise during pregnancy may be protective for DRA. It is sensible to avoid loaded rectus abdominus and abdominal oblique muscle exercises while you are pregnant and until 6 weeks postpartum. This includes heavy weights, planks and sit ups.

Effective activation of the transverse abdominus is important to tension the linea alba. The pelvic floor muscle is also an important core muscle and normally works automatically with the deep core later. Following a strengthening program and actively contracting the pelvic floor muscles and transverse abdominus together during activities which may otherwise result in an abdominal bulge, such as lifting or pushing a buggy from a standstill, will lessen the stretch forces on the linea alba.

After 6 weeks postnatal, you should gradually retrain the full abdominal wall including the transverse abdominus. Light weights and low impact exercise is recommended from 6 weeks postnatally, with a graduated return to high impact and heavier exercise from 3 months post natally.

Understanding how to correctly exercise the transversus abdominus and pelvic floor muscles, and progressing exercises through pregnancy and beyond is key to a stronger abdominal wall. Before, during or after pregnancy, a physiotherapy session to master the exercises are a good investment for the future.

A thorough examination comprised of specific questions and physical tests can help to diagnose the cause of your pelvic pain. A treatment plan would then be discussed and implemented, to help you towards being pain free and get you back to performing your desired activities. A fundamental part of the treatment plan is explaining the cause of pain and ways to manage it.

Treatment could include hands-on therapy (joint mobilisation/soft tissue massage), a programme of stretches or strength based exercises, Taping, Acupuncture, Ultrasound or perhaps Shockwave Therapy (if appropriate).

If further investigations such as MRI, Ultrasound scan, blood tests or X-rays are required, our Physiotherapists can point you in the right direction. If the Physiotherapist feels you need to see another health professional (such as an Orthopaedic Consultant or Rheumatologist), they will ensure you see the right person via our vast network and close links with consultants.

So, if you have been struggling recently with pelvic pain, click here to contact us so we can help you get better!

We usually call you back within the hour during normal working hours

We usually respond within the hour during normal working hours